Read Time: 4-minutes

Happy Saturday,

Here is this week’s edition of 6-Point Saturday — financial insights to help you make smarter money decisions.

Table of Contents*

*Clickable in the online version.

Point #1 — The Financial Cost of Standing Still

“After a poetry reading, the poet David Whyte was approached by a crowd-member who turned out to be a high-level executive in corporate America. ‘I want to hire you to give talks at my company,’ the man said, adding that they’d not only pay him extremely well, but would cover travel and accommodation costs too.

Though struggling to make ends meet as a poet, Whyte had no interest in the offer.

‘Where I grew up,’ he explained, ‘anything that was part of the corporate world was the enemy to art.’

Whyte grew up in a ‘raving socialist’ part of Northern England. ‘In fact,’ Whyte explained, ‘the Luddites used to meet in the field next to where I grew up to train before they marched across the fields and broke up the new weaving machinery they thought was taking their jobs.

So in the milieu I grew up with, I inherited the belief that the corporate world was filled with big, bad, overreaching, all too powerful, inhuman people.’

To enter that world, Whyte said, ‘was to sell yourself out. It was to compromise and sully your art. It was simply not what serious artists do.

So I told the man, ‘No, I’m not interested. But I am interested in why you would want to hire me.’

And he said a beautiful thing actually. He said, ‘The language we have in that world is not large enough for the territory that we’ve entered. And I just heard the language, in your poetry, that’s large enough.’’

Though moved by the man’s interest, Whyte said, ‘it still didn’t bump me out of my inherited enclosure of what it meant to be an artist.’

Whyte returned to Whidbey Island, the small island north of Seattle where he was living at the time. A couple weeks later, he got a phone call from the exec, who tracked down Whyte’s contact information to reiterate his interest in hiring him.

When Whyte turned him down again, ‘the man said, ‘Right, I’m coming out to Whidbey Island then to see you.’’

The following weekend, the man made the trip, ‘and we had a great old conversation. He was a very imaginative man. Very funny. Very insightful. Very kind and sincere.’ Not at all like the big, bad, overreaching, all too powerful, inhuman caricature Whyte had inherited from his upbringing.

So Whyte finally agreed to give a talk at the man’s company—the beginning of what has now been decades of bringing his poetry into corporations around the world.

‘And to my surprise at first, then to my gratification, I found that I didn’t have to compromise my work at all.’

If it weren’t for the persistent executive, Whyte would’ve missed out on so many opportunities.

That’s the problem with status quo bias — the mental bias that makes people prefer the familiar, even when trying something new would be beneficial.

It robs you of your future. This shows up in our finances everywhere:

Beliefs: Whyte described his beliefs about what it meant to be an artist and the corporate world as an “inherited enclosure.” The beliefs you pick up about money from family & friends can trap you. If your parents lost money in the stock market, you might be overly conservative. If you have always heard “we can’t afford that,” even when it was more a matter of priorities, you might struggle with a scarcity mindset. These inherited money beliefs can keep you trapped in suboptimal financial behaviors if you stick with the status quo.

Values: Never questioning the money values from your upbringing or peer group. For example, inheriting extreme frugality (‘never pay for convenience’) when your income now justifies outsourcing tasks to free up time. Or taking multiple costly vacations like your colleagues, even though you’d rather prioritize early retirement or starting a side business.

Investing: Keeping old 401(k)s with former employers (when consolidating, better investments, or lower fees are available), neglecting rebalancing, or clinging to an underperforming stock pick.

Cash management: Leaving savings in low-interest accounts when high-yield savings offer 4%.

Insurance: Never shopping around for homeowners/auto insurance or right-sizing your insurance needs after significant life changes.

Debt: Using balance transfer cards without addressing an underlying spending issue.

Spending: Some individuals get so used to saving that when they achieve financial independence, it’s challenging to let themselves spend.

Legal documents: Not getting a basic will, financial power of attorney, healthcare power of attorney, and advanced medical directives in place.

Combined, these missteps can cost you hundreds of thousands over your career.

So, how do you avoid this common cognitive bias?

Let’s look at 5 ways to overcome status quo bias to grow your wealth…

Point #2 — 5 Ways to Overcome ‘Status Quo’ Bias

Research shows 5 ways to overcome status quo bias:

Use “If-Then” Planning

Change the Default

Pre-Commit

Reduce Friction

Reframe Inaction as a Loss

1. Use “If-Then” Planning

What it is: Create specific statements linking situations to actions: "If X happens, then I will do Y."

Why it works: A 2006 meta-analysis (Gollwitzer and Sheeran) of 94 studies found implementation intentions had a “medium-to-large effect” on goal achievement. If-then plans create automatic triggers that help you execute on your good intentions.

3 ways to apply it:

"If I get my bonus, then I'll immediately transfer 50% to my checking account to treat myself and 50% to investments."

"If I'm considering spending over $200 on a ‘non-essential,’ then I'll wait 48 hours before I make the decision."

"If my portfolio drifts over X% from my target allocation, then I will rebalance."

2. Change the Default

What it is: Make beneficial choices the default.

Why it works: A study (Madrian & Shea, 2001) found that switching from opt-in to automatic 401(k) enrollment significantly increased participation and contribution rates. Your brain treats defaults as implicit recommendations. Rather than requiring willpower to make good choices, you're now requiring willpower to make bad ones.

Three ways to apply it:

Do not opt out of retirement plan contributions

Use auto escalation features to automatically increase your 401(k) contributions (1-2% annual bumps) at regular intervals

Switch bills to auto-pay

3. Pre-Commit

What it is: Make commitments now for your future self, removing the option to procrastinate later.

Why it works: A "Save More Tomorrow" program (Thaler and Benartzi, 2003) let employees pre-commit to increasing retirement contributions with future raises, dramatically increasing savings—more than 3X. You're better at making rational decisions for ‘Future You’ than ‘Present You’ (signing up to start a diet next week is a lot easier than declining dessert at lunch today). Once you sign up to start saving more, it takes effort to change your new status quo.

3 ways to pre-commit:

Schedule an annual financial review as a recurring calendar event

Set up an auto-transfer to begin or continue building your Stability Fund (Emergency Fund)

Tell one person your financial goal who'll follow up with you

4. Reduce Friction

What it is: Eliminate unnecessary steps and complexity (friction) between you and beneficial financial decisions.

Why it works: Richard Thaler’s research led him to call unnecessary complexity "sludge": every extra step—every login, form, or phone call—is a chance for status quo bias to win.

3 ways to reduce friction:

Consider a target-date fund if investment choices overwhelm you (done beats perfect)

Consolidate old 401(k) accounts into an IRA or your current plan

Set up account aggregation so one login shows everything

5. Reframe Inaction as a Loss

What it is: Framing inaction as a loss and quantifying the actual dollar cost of staying put makes inaction feel riskier than action.

Why it works: Loss aversion—preferring avoiding losses over acquiring equivalent gains—can break status quo bias—if you frame the decision as a loss. When you see what inaction actually costs, the "safe" choice clearly becomes expensive.

3 ways to reframe inaction:

Determine the cost of delayed investing: Investing $200/month for 20 years at an 8% return is $110,000. Waiting 5 years to get started results in only $65,000, or losing $45,000 in gains (!).

Annualize the costs of unused subscriptions (streaming services, gyms, etc.): $40 in unused monthly subscriptions is nearly $500 over the course of a year.

Calculate savings opportunity cost: Leaving your $5k savings in a near-zero interest bank account ‘you’ve always used’ versus transferring to a 4% high-yield savings account costs you $400 in missed opportunity.

Start by asking: “Which 1 of these strategies appeals to me?“

👉 Get money-saving, wealth-building tips like these every Saturday morning. Join here.

Point #3 — “My Biggest Investing Mistake”

“When I was first exposed to the idea of investing, I thought that this advice made sense: buy the stock of the product that you support. I mean, on surface level, it kinda makes sense, but it still involves alot of research and understanding. That stock is Starbucks. I bought it at one of their highest points. I still hold it today because it's just on an app that I don't use anymore, and it's just that one stock in the app.”

A great example of the impact of status quo bias.

Instead of re-evaluating whether it makes sense to continue holding the position, inertia takes over.

They continue holding onto it because it’s on an old app they no longer use.

How can you overcome this?

Ask yourself these questions:

If you had the equivalent amount of value in the stock position in cash, would you invest in Starbucks today? If the answer is no, that’s your cue to move on.

How much of a return are you missing out on by continuing to hold? This reframes inaction as a lost opportunity.

Point #4 — Investing Risk Tolerance vs. Risk Capacity

One way to see if your inherited beliefs are impacting your investing is to do a more robust analysis of your approach and attitude towards investment risk.

While you’ve probably heard the term “Risk Tolerance,” “Risk Capacity” may be a newer concept for you.

Let’s define each and see how they interact with each other.

Risk tolerance is generally defined as an investor’s willingness, both psychological and emotional, to take on investment risk as it relates to uncertainty and market volatility. This measure helps form the foundation for building a portfolio’s mix of assets.

On the other hand, risk capacity is an investor’s ability to take on risk as anchored by their objective financial resources. This includes the investor’s assets, debts, income, emergency fund, insurance, and time horizon.

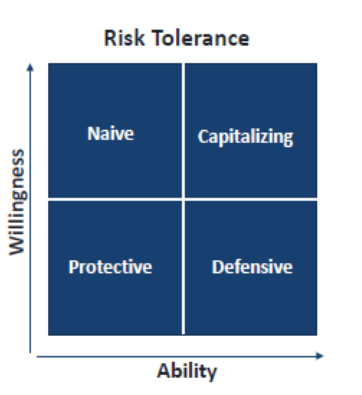

What results is a matrix that investor Howard Marks shared in his latest memo:

How to think about each quadrant:

An investor in the upper-right quadrant has a high risk capacity or financial ability to take on risk and the willingness to capitalize on this.

If that investor has a lower risk tolerance (lower-right), then he or she has a defensive approach, because risk capacity suggests otherwise.

When an investor has a low risk capacity to bear risk, but a high willingness, this individual could be described as “Naive,” because they’re financial position doesn’t support their risk tolerance.

Finally, an investor with low risk capacity and a low tolerance is considered “Protective” because of his or her low ability and willingness to take on risk.

Bottom line: Assessing where you stand both in your risk tolerance and risk capacity can give you greater confidence in your strategy.

Point #5 — Quotes of the Week

Continuing the “Status Quo Bias” theme, which of these is your favorite?

Point #6 — My Questions of the Week

What's a past financial decision you “finally” took action on after letting it linger (e.g., cancelling an unused subscription, reinvesting proceeds from an investment you cut losses on, etc) that felt great and was a smart financial move?

What's the smallest action step you could take today on a similar issue in your finances?

Reply to let me know! I read every response.

Thanks for reading — I hope you found a helpful idea or two.

I’ll see you next Saturday with more.

Have a great weekend,

Benjamin Daniel, CFP®

Founder, Money Wisdom

P.S. Want to take control of your money, stop stressing about your expenses, & feel confident about your financial future? There are 2 ways I can help you:

Financial Health Check: Get your biggest money questions answered, understand where you stand financially, and get a personalized action plan from a CFP® professional. Book a free Intro Call here to see if you’re a good fit.

Financial Coaching: If you’d like some accountability in getting your finances into shape, engage in financial coaching. Build the habits & systems to help you start building wealth, pay off debt, and feel confident about achieving your goals. Reply to this email and say “Coaching” to join the waitlist.

Disclaimer:

This material is not investment or tax advice. No responsibility for loss occasioned to any person or corporate body acting or refraining to act as a result of reading this material can be accepted by the publisher.

How helpful was today's newsletter?

👉 Is there another topic(s) you would like me to cover? If so, reply to this email & let me know—I read & respond to ALL emails.